September 26, 2019

The USDA projects a 46% reduction in chickpea production this year, but given the weather, it may end up being more than that.

Chickpea harvest in the Palouse.

Wet weather has made this an especially challenging harvest for North American pulse growers. In the case of chickpeas, Max Hinrichs of Hinrichs Trading reports that harvest progress has fallen two weeks behind the average pace. And he is in a position to know. Max’s family business handles approximately 20% of the chickpea production in the United States.

“This is shaping up to be the coolest and wettest September we’ve had in five or six years,” he tells GPC from his office in Pullman, Washington, in the famed Palouse region of the United States’ Pacific Northwest (PNW), a land of rolling hills and highly fertile soil where a good part of the country’s peas, lentils and chickpeas are grown.

“The problem with the rain at this time of the year is that the days are getting shorter and the nights cooler, so it takes longer to dry out,” he continues. “We’re only around 35% harvested in the PNW.”

The wet weather is a problem not only in the Pacific Northwest, but also in the Northern Plains, the other major chickpea growing area in the U.S. The top pulse growing states there are North Dakota and Montana. The situation appears to be especially bad in the latter.

“I was talking to people in North Dakota the other day. They had six inches of rain in the last ten days. They’re reporting almost no harvest and the majority of the crop is showing sprouting damage,” says Max.

According to the USDSA’s September 12thCrop Production report, North Dakota seeded 41,400 of the 445,200 acres planted to chickpeas this year; the PNW seeded 196,000 acres, which is incidentally the same as the area Montana seeded. Max reports harvest progress in Montana at 50%.

“It’s raining there, too,” he says. “Every time it rains, it’s three or four days before you can get back to it. With the shorter days and cooler weather, its not till about 11 a.m. that things start to dry out.”

The U.S. chickpea harvest normally wraps up around September 25th, but, given the wet conditions, Max sees the last of the crop coming off the fields as late as October 9th. Quality is the major concern at this point. In the PNW and Montana, the crop appears to be fine. But in North and South Dakota, and to a lesser extent Nebraska and eastern Montana, there is a high incidence of sprouting damage.

“Nobody’s that excited about what’s happening out there,” Max relates. “The crop looks damaged. And if its damaged in the Northern Plains, the Canadian’s north of us have to have the same problem. Talking to different Canadian companies, it sounds like it’s a similar situation in Saskatchewan.”

Should North America have a poor harvest, the one silver lining is that it might take some of the pressure off of prices, which are presently being suppressed by the weight of abundant global supplies. In the case of the U.S., old crop carryover is estimated at a burdensome 305,000 MT.

Reached by telephone in mid-September, Max shared his thoughts on the market outlook for U.S. chickpeas in 2019/20.

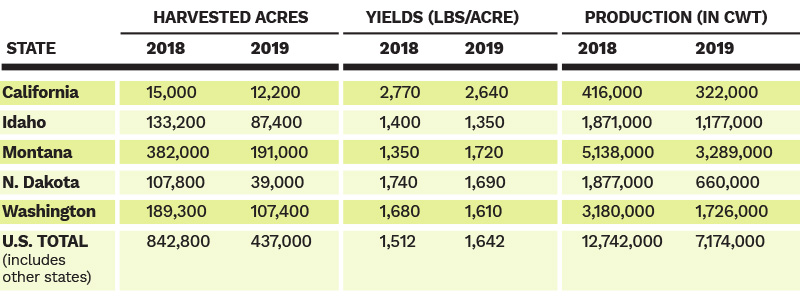

Source: USDA Crop Production report, September 12, 2019.

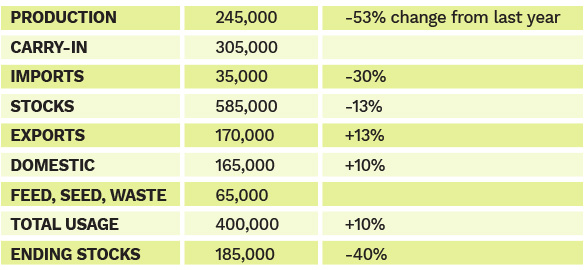

Source: Pulses 2019 presentation on kabuli chickpeas.

Max: I grew up in eastern Washington on the family farm, where we processed both peas and lentils, and later added chickpeas. You could say I grew up in the pulse industry. From there, I wanted to do more on international sales, and so I spent five years in San Francisco working for HP Schmid, an international trading company. Then I was hired by a Swiss company by the name of Andre that had a U.S. company by the name of Finora. I spent seven years working for the Finora Group in Denver with Kent Hobbs. We managed the Mexican chickpea position for Andre for seven years. I was then hired by Archer Daniels Midland and spent ten years as a trader in their edible bean and package oils division.

After that, I went back into the family business, Hinrichs Trading, to team up with my brother Phil Hinrichs and our father Bob Hinrichs, and helped grow the chickpea business both domestically and internationally. The company had been exporting before then, but through different brokers and never knowing exactly where the product was going. I was able to change that and put Hinrichs Trading more in a direct line with customers.

Max: It’s a family business that is now in its fifth generation. There’s been a lot of Maxes: my great grandfather Max, my grandfather Max, my dad and his brother, my brother Phil and myself, and now Phil’s son Kyle.

My great grandfather is the one who started it all. He immigrated to the U.S. form Hamburg, Germany, and homesteaded in the Pullman area. We started out as farmers. In addition to farming, my great grandfather Max also did some grass seed processing on the side. We used to work with peas, lentils, wheat and canola. We didn’t start with chickpeas until my father went to Mexico and brought back some seed. He went down there and worked with Granos La Macarena to select the right variety for the Palouse. That was in the late ’70s. But they really never took off at that time. It was another 15 years until chickpeas got more popular and then finally in the late ’90s they were mainstreamed here in the Palouse. As the chickpea business started growing, we were able to capitalize on it and we dropped the other crops and strictly processed chickpeas. We can always go back to the other items, but our main line is basically chickpeas now. We also process a few pinto beans on a contract basis. But with the hummus industry and the boom in domestic consumption, that gave us a lot of opportunity to expand the chickpea business. We’ve always kind of been the leader in U.S. chickpeas. Other companies process peas, lentils and chickpeas. We just focus on chickpeas.

Max: Yes, well, the USDA has the harvested area at 437,000 acres, which we think sounds right. That compares to 842,800 acres last year. Yields, though, are the wildcard. The USDA has the average at around 1,600 lbs./acre and we think it’s going to be closer to 1,200 or 1,300 lbs./acre. So that would give us a crop of less than 5.7 million cwt, while the USDA is forecasting production of 7 million cwt.

Max: It’s hard to tell. It has kind of been a race to the bottom. We have carryover and talk of more production. That has buyers sitting on the sidelines. We’ve been waiting for a weather market and maybe we have it now. We’ll see what happens going forward, but I think this market hit bottom about 30 days ago.

Max: In Spain, I think we’ve got a good opportunity to continue placing about the same tonnage we did last year. The size distribution may change a little bit, but I think we’ve built a good base there.

In India, I don’t expect any product to go there. I mean, some people will have permits, but I expect more product from Canada to go in that direction. And I think this will help the U.S. a lot.

Max: I think the U.S. market will grow by 8 to 10% this year. Some of that growth is due to USDA programs to help the industry. But it is also the continuing growth of the hummus sector and new product launches, whether it’s chickpea snacks or an ingredient in a specialty drink or something to do with protein. There is also the pet food industry, which is flat this year, but had been a growing sector for the past five years or so.

We’ve been seeing 8 to 10% growth in the domestic market for several years now. Seven years ago, there was a spike where demand really took off. The big international companies were promoting hummus. They had the shelf space and they put advertising dollars behind it.

There is also the organic side. That’s another growing sector for chickpeas.

Max: We are really staying on top of the weather right now. Second is Canada; a lot depends on their crop. Third is Mexico; we’ll have to see how much they plant next cycle because until they get relief from their burdensome inventories, I don’t see anyone pushing chickpeas. And then there is the crop out of Argentina that will be harvested in the coming months.

Everybody is in the same position. We all have a little extra product leftover from the 2018 crop. Maybe in 12 to 18 months, there’s an opportunity for a turnaround.

There’s a lot going on in the world right now and everyone in the pulse business is looking at the chickpea market and trying to figure out if it has bottomed or if we have more to go, and what’s going on with the harvest at these different origins. It’s going to be interesting to see where things end up in about 20 days. By then, we’ll know how the harvest went, especially in North Dakota. Here in the PNW, hopefully it stops raining and we can get in there and harvest another beautiful crop.

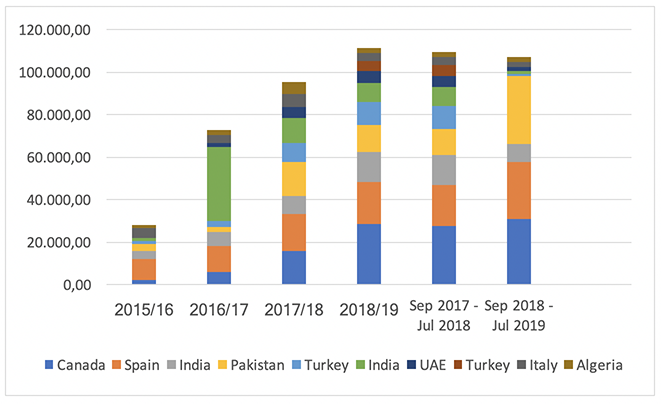

Source: USDA FAS GATS

Disclaimer: The opinions or views expressed in this publication are those of the authors or quoted persons. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Global Pulse Confederation or its members.